Lessons We Can Learn From Aviation Checklists

Checklist Best Practices | By | 26 Apr 2016 | 6 minute read

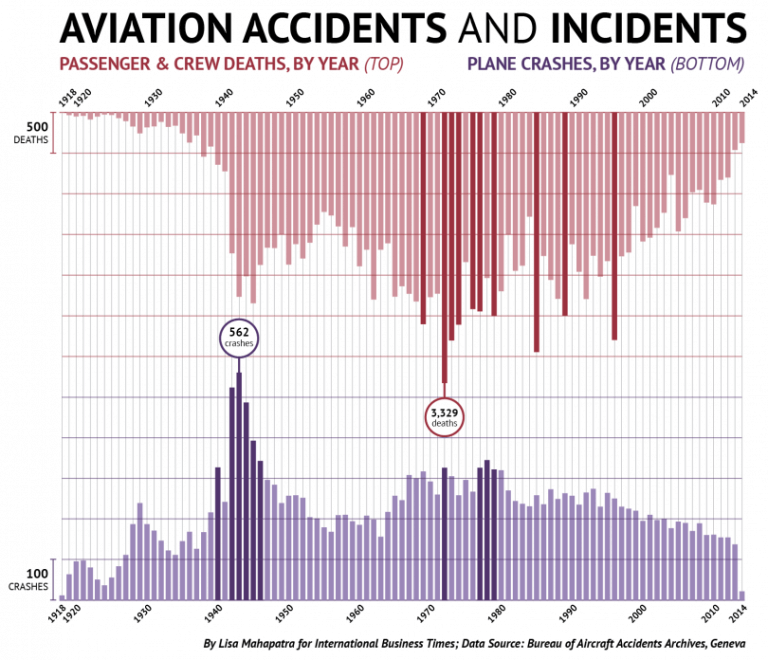

Over the last 30 years, aviation has radically transformed – an industry where safety is the number-one priority. Aircraft accidents have been on a steady decline since the 1980s after aviation checklists were introduced to flight crews.

But checklists alone cannot make a workplace safe. In the aviation industry, unavoidable human error was rejected long ago, replacing this mindset with a strong safety culture and a reliance on proven procedures.

The emergence of COVID-19 has further exacerbated operational challenges for pilots and aviation crew. To retain public trust, the aviation industry must keep safety and hygiene firmly in mind at all times.

Why Do Pilots Use Checklists

When issues arise mid-flight, the natural response is typically to troubleshoot and rely on judgment, as Captain Chesley Sullenberger (aka Captain Sully) did when navigating an emergency aircraft landing on the Hudson River.

Pilots turn to checklists for two reasons:

- They’re trained to do so instead of relying on memory.

- Checklists are proven to work. Pilots have learned to trust the checklist, even when faced with catastrophe.

What Makes a Good Checklist?

The best-selling book The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande advocates for using checklists as teams in our professional lives. Checklists dramatically raise effectiveness and reduce errors. This is true even when experts are in charge. The book notes that in our complex age, no one person can remember all the essential steps to perform a complex procedure. Checklists provide a cognitive safety net, catching all the mental flaws that are inherent in us as human beings.

Within the book, Gawande describes how Boeing issues over 100 meticulously put-together checklists each year.

The Checklist Manifesto notes that bad checklists are vague, imprecise, and impractical – spelling out every single step. Good checklists, on the other hand, are precise, efficient, to the point, and easy to use in the most difficult situations. Gawande notes that checklists alone cannot fly a plane, but they can make priorities clearer and prompt people to function better as a team.

Checklists alone cannot fly a plane, but they can make priorities clearer and prompt people to function better as a team.

Gawande’s research explains that experts often oppose the idea of reducing their complex jobs to a simple checklist. Surgeons, in particular, frequently think that relying on their own expertise or hard-earned knowledge is the only way to successfully do their job. When it comes to aviation, pilots could decide to try harder not to crash their plane, or dismiss previous crashes as a result of inexperience. But this is not sustainable – or safe. Instead, successful pilots accept their mortality and therefore are prone to human error, so choose a checklist as their primary tool.

Guidelines for Aviation Checklists

Gawunde interviews Daniel Boorman, Production Test Pilot at Boeing, a veteran pilot who spent two decades developing checklists and flight deck controls. He has studied thousands of aviation crashes and near crashes, developing the science of avoiding human error. They break checklists out into ‘normal’ everyday actions, including a pre-flight checklist, but also into ‘non-normal’ checklists covering emergency situations.

Here are some of the guidelines established by Boorman and tips that you can apply to your own checklists:

Define clear pause points

Pause points determine when a checklist should be used – when starting a new task, for example.

Determine whether your checklist is a do-confirm vs read-do checklist

Do-confirm is generally used when experienced team members have run through the necessary steps within the checklist and confirmed they have been actioned. With a read-do checklist, team members perform the tasks as they’re reading through the checklist, similar to a recipe or a regular to-do list template.

Stick to 5 to 9 items per checklist

Boorman stresses that this is not an absolute rule, but humans’ working memory is generally between 5-9 items. In some situations, you may have more time to perform a task and so can expand the checklist. If the list is too long, you risk having people shortcut some of the items. Fit the checklist on one page, and keep it free of unnecessary clutter.

Focus on ‘killer items’

These are the most crucial checklist items, but are also frequently overlooked. This is why testing checklists and gathering data is so important, so you can identify where these ‘killer items’ are.

Use simple and precise wording

Use occupation-specific language – terms the reader will be very familiar with.

Most importantly, test your checklist

Testing the checklist ensures you’ve identified all the right pause points, kept it short enough, and that it is easy to understand. The aim of implementing checklists is not simply to have people read through it and check off items. The aim is to incite a cultural change by enhancing teamwork, increasing communication, and changing the definitions of authority within a team.

The aviation industry has seen clear safety improvements by implementing checklists into their everyday processes, but they also experienced a cultural shift that changed the way teams work together. Checklists have redistributed the responsibility of safety among team members by successfully leveraging the team’s collective knowledge.

Checklists can keep us safe, and being able to collaborate with team members in real-time can make all the difference, especially when it comes to having eyes and ears both on the ground and in the air.

Preventing Safety Breaches

Before the introduction of a crew management system in the 1980s, a series of aircraft accidents took place that could have been avoided. Error was once viewed as a weakness and people looked to blame as a result. Now in the cockpit, errors are dealt with immediately and turned into learning exercises where the team can evaluate them and manage them better next time.

“Blame is the enemy of safety. It misses opportunities to learn.”

– Captain Chesley Sullenberger (aka Captain Sully), Pilot, at the SafetyCulture Virtual Summit

With the crew management system, the roles were redefined. The captain focused more on managing the team and their efficiency than the individual tasks he needed to complete. The role of the co-pilot and team members were to think critically – not blindly obey orders, but to monitor issues and have a voice in decision-making.

The transformation has made aviation safer due to shifting the definitions of authority. Previously, the culture was that the captain was ‘king’ and his subordinates were not to question his methods. But today, the culture ingrained is to call out any mistakes, regardless of rank. The result? Fewer airplane crashes and better working relationships. A simple concept that can be applied to your own company to ensure each employee is accountable.

Team Intelligence

Instead of focusing on hierarchy, the industry puts emphasis on individual intelligence to foster team intelligence. In the old days, young pilots would be too scared to point out errors from their high-ranking officials, causing many critical errors to slide through.

Possessing emotional intelligence in the workplace is seen as a vital skill when it comes to working in teams. While it’s an important concept, creating genuine teamwork requires moving beyond the focus on our own individual emotional intelligence, to that of ‘team intelligence‘. A Cornell research paper states that emotional intelligence on its own is not enough. Team intelligence goes a little deeper, where individual members of a team must learn, teach, communicate, and think together, regardless of their authority.

In the case of the 2009 US Airways Flight 1549, the crew managed to safely evacuate 154 passengers in minutes due to effective teamwork and checklist procedures put in place.

Another important aspect of teamwork within the aviation industry is reporting all errors. In doing so, critical data for investigations can be used to make vital improvements to safety. The aviation industry routinely interrogates errors to avoid the same occurrence in the future. Where there is a significant blame culture, human error will continue to take place.

One way to encourage accountability is to build document workflows into your inspections, where everyone can take ownership and see what has been done, in real time.

Change doesn’t happen overnight

Air accidents peaked in the 1940s, but have been on a steady decline since the 1980s.

The desire to develop a transformation in the industry didn’t occur overnight. Stakeholders were called in to refine and improve the current system, including unions, researchers, company officials, government officials, and academics over a few years and many workshops. The aviation safety curriculum was supported by decades of research and ongoing reform.

Applying these Lessons to your Own Business

Avoidable failures are everywhere, particularly in high-risk industries such as aviation. The volume and complexity of what we know today has exceeded our ability to deliver many procedures safely.

The key takeaway we can learn from aviation is that a follow-up plan, regular briefings, teamwork procedures, and ongoing communication has been the game changer for the aviation industry. And they have proved time and time again that having an emphasis on team intelligence and effective procedures like operational reports and checklists can ensure teams are on the same page and operating at their best.

Want to learn more about checklists?

- How to make an effective checklist

- How to create a good aviation checklist

- Try building your own checklist with SafetyCulture

Important Notice

The information contained in this article is general in nature and you should consider whether the information is appropriate to your specific needs. Legal and other matters referred to in this article are based on our interpretation of laws existing at the time and should not be relied on in place of professional advice. We are not responsible for the content of any site owned by a third party that may be linked to this article. SafetyCulture disclaims all liability (except for any liability which by law cannot be excluded) for any error, inaccuracy, or omission from the information contained in this article, any site linked to this article, and any loss or damage suffered by any person directly or indirectly through relying on this information.